Archived Article Detail

By Thomas P. Moore

WHAT’S NEW IN THE MINERAL WORLD ARCHIVE – posted on 4/27/2007

Here is a look at some mineralogical developments on the web as of late April 2007. The selection of items is without (much) redundancy with anything on the list of new discoveries noted during the Tucson Show—you will hear about them in the show report that will appear, as usual, in the May-June 2007 issue, just now going to press.

Having just completed a move, I have a new e-mail address. It will be reported in the May-June issue, but might as well be repeated here. I am ever-receptive to feedback of any sort, particularly concerning new finds which may be grist for this mill, at tpmoore1@cox.net.

What’s New Online

At the very end of the June 30, 2006 edition of this column I flashed some news of major gold discoveries at the Round Mountain mine, Nye County, Nevada—a profitable operation which is shaping up to be one of the major specimen-gold localities of the present decade. The mine’s management has sometimes expressed distress at the growing fame of Round Mountain with those who seek crystallized gold specimens (that’s us, comrades), but nevertheless, this past March, California dealer John Veevaert (of Trinity Minerals, www.trinityminerals.com) was invited to visit the mine to participate in a sealed-bid auction for 56 lots of specimen-quality gold. Rather to his surprise he came out high bidder on one of the lots, and to his further surprise it turned out to harbor some absolutely first-rate display pieces of miniature and thumbnail size. You may see pictures of many of these specimens on his site, although already the majority are marked “sold,” and no wonder: the gold forms extremely sharp, hoppered, octahedral crystals to 5 mm individually, and some groups have utterly brilliant, razor-sharp, mirror-faced, blocky crystals to 2 mm. Some specimens are loose, elongated spinel-law twins with subordinate gold crystals growing in rows along their sides; others are flattened plates taking the form of undulating, lustrous “leaves” with trigon faces faintly evident on them (evidence that they, too, are distorted spinel-law twins), rimmed by rows of small crystals in parallel growth; still others are treelike forms built of loosely attached, elongated crystals. The colors vary from rich, deep golden yellow to much paler yellow, the gold in the latter specimens being silver-rich enough to be called electrum (gold with more than 20% Ag). John’s prices are, I’d say, even better than “reasonable,” ranging from $150 for a small thumbnail to around $1,000 for a dazzling miniature. These are the best crystallized gold specimens to come out of anywhere-but-California in a long long time.

At the very end of the June 30, 2006 edition of this column I flashed some news of major gold discoveries at the Round Mountain mine, Nye County, Nevada—a profitable operation which is shaping up to be one of the major specimen-gold localities of the present decade. The mine’s management has sometimes expressed distress at the growing fame of Round Mountain with those who seek crystallized gold specimens (that’s us, comrades), but nevertheless, this past March, California dealer John Veevaert (of Trinity Minerals, www.trinityminerals.com) was invited to visit the mine to participate in a sealed-bid auction for 56 lots of specimen-quality gold. Rather to his surprise he came out high bidder on one of the lots, and to his further surprise it turned out to harbor some absolutely first-rate display pieces of miniature and thumbnail size. You may see pictures of many of these specimens on his site, although already the majority are marked “sold,” and no wonder: the gold forms extremely sharp, hoppered, octahedral crystals to 5 mm individually, and some groups have utterly brilliant, razor-sharp, mirror-faced, blocky crystals to 2 mm. Some specimens are loose, elongated spinel-law twins with subordinate gold crystals growing in rows along their sides; others are flattened plates taking the form of undulating, lustrous “leaves” with trigon faces faintly evident on them (evidence that they, too, are distorted spinel-law twins), rimmed by rows of small crystals in parallel growth; still others are treelike forms built of loosely attached, elongated crystals. The colors vary from rich, deep golden yellow to much paler yellow, the gold in the latter specimens being silver-rich enough to be called electrum (gold with more than 20% Ag). John’s prices are, I’d say, even better than “reasonable,” ranging from $150 for a small thumbnail to around $1,000 for a dazzling miniature. These are the best crystallized gold specimens to come out of anywhere-but-California in a long long time.

Another site run by John Veevaert is called “Tsumeb Minerals” (www.tsumeb.com). This is now the parking place for 145 mostly small but altogether intriguing Tsumeb specimens which John purchased when he visited Tucson-based Tsumeb-mineral collector Marshall Sussman during the Tucson Show. For prices which, again, are better than “reasonable,” a widely varied Tsumeb assemblage is offered here; specifically, you can get a nice calcite thumbnail for about $20, but you can also pick up a wonderful cabinet specimen of anglesite/cerussite for more than $1,000. Most of the specimen prices cluster in the lower part of that range, and excellent thumbnails prevail, especially of mimetite, of which there are 43 amazingly diverse examples, showing this species in every habit you’ve ever seen from Tsumeb, and some which you probably haven’t. Besides good-to-superb examples of the “standard” species from Tsumeb, this lot includes clusters of gemmy yellow willemite crystals, pine-forest-like growths of mottramite, shiny grape-like clusters of copper crystals, two thumbnail-size mats of glistening red-brown ludlockite, a few eccentric-looking galenas, and two chalcocites to remind you that Tsumeb on a good day is right up there with Cornwall, Connecticut and Wisconsin when it comes to that species.

Good news about anything having to do with Iran is scarce these days … but, you know, there is what looks like a pretty serious locality for epidote near the Iranian city of Qum (or Qom), in Markazi Province. Attractive epidote specimens from this place were brought to the Munich Show in 2001 and 2002, and the show reports in Mineralien Welt passed on what was apparently misinformation that the locality lies in the Zagros Mountains—in fact, those mountains lie far to the south of Qum. Now the dealership Mineralium.com (www.mineralium.com) informs us that the epidote specimens were collected in the year 2000 on “Mount Khowrin, Kuhandan, Saveh, Tafresh, Markazi Province”: my atlas tells me that Savah and Tafresh are towns respectively 60 km northwest and 90 km west of Qum. The specimens offered, of miniature to small-cabinet size, show sleek, highly lustrous, bladed epidote crystals clustered thickly on olive-green matrix of what’s called a “pistazite skarn”— Bayliss’ Glossary of Obsolete Mineral Names (2000) says that “pistazite” is an obsolete term for Fe-rich clinozoisite. As the picture here shows, these specimens are extremely handsome, and the dealership adds that the locality “is no longer in operation.” Especially if that’s true, what we have here are pretty good deals for prices between 79 and 289 €.

Good news about anything having to do with Iran is scarce these days … but, you know, there is what looks like a pretty serious locality for epidote near the Iranian city of Qum (or Qom), in Markazi Province. Attractive epidote specimens from this place were brought to the Munich Show in 2001 and 2002, and the show reports in Mineralien Welt passed on what was apparently misinformation that the locality lies in the Zagros Mountains—in fact, those mountains lie far to the south of Qum. Now the dealership Mineralium.com (www.mineralium.com) informs us that the epidote specimens were collected in the year 2000 on “Mount Khowrin, Kuhandan, Saveh, Tafresh, Markazi Province”: my atlas tells me that Savah and Tafresh are towns respectively 60 km northwest and 90 km west of Qum. The specimens offered, of miniature to small-cabinet size, show sleek, highly lustrous, bladed epidote crystals clustered thickly on olive-green matrix of what’s called a “pistazite skarn”— Bayliss’ Glossary of Obsolete Mineral Names (2000) says that “pistazite” is an obsolete term for Fe-rich clinozoisite. As the picture here shows, these specimens are extremely handsome, and the dealership adds that the locality “is no longer in operation.” Especially if that’s true, what we have here are pretty good deals for prices between 79 and 289 €.

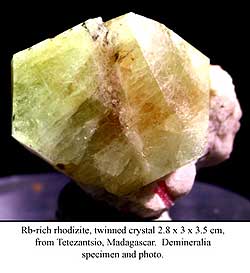

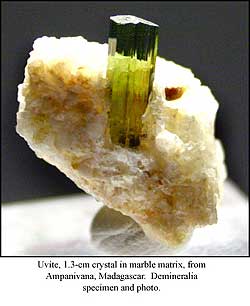

The Italian dealership Demineralia (www.demineralia.com) has always been strong on the minerals of Madagascar, and the recent Madagascar page of its site features, sure enough, some fine things. These are mostly sharp, thumbnail-size crystals, quite gemmy when they can be, of many species, including prominently liddicoatite, chrysoberyl, pezzottaite, corundum, londonite and ferrocolumbite. Pictured here is an especially jazzy-looking, twinned crystal of rubidium-rich rhodizite from Tetezantsio, and, most surprisingly (at least to me), a green, totally gemmy, terminated 1.3-cm prism of uvite, rising from white marble matrix, from Ampanivana. Stay tuned for the Tucson Show report, with some news of exciting new Madagascar (Malagasque?) liddicoatite occurrences as were represented at the Big Show.

The Italian dealership Demineralia (www.demineralia.com) has always been strong on the minerals of Madagascar, and the recent Madagascar page of its site features, sure enough, some fine things. These are mostly sharp, thumbnail-size crystals, quite gemmy when they can be, of many species, including prominently liddicoatite, chrysoberyl, pezzottaite, corundum, londonite and ferrocolumbite. Pictured here is an especially jazzy-looking, twinned crystal of rubidium-rich rhodizite from Tetezantsio, and, most surprisingly (at least to me), a green, totally gemmy, terminated 1.3-cm prism of uvite, rising from white marble matrix, from Ampanivana. Stay tuned for the Tucson Show report, with some news of exciting new Madagascar (Malagasque?) liddicoatite occurrences as were represented at the Big Show.

A similar sort of viewing experience, with gem crystals littered all over your computer screen—although this time the crystals hail from Myanmar (Burma)—is offered by a new website, that of Crystal Treasure (crystal-treasure.com), based in Göttingen, Germany. The site, being new, does have its frustrating elements: pictures of specimens are too small and too often blurry (but, after all, the crystals are small and often best shown off in swarms); specific localities within the gem tract are never given (but then how frequently are they given, when you’ve seen selections of this material?). Anyway, the huge numbers of loose, commonly quite tiny but generally sharp, gem crystals expand our sense of the richness of the mysterious Mogok gem tract. The visitor can ogle loose, splintery, gemmy green crystals of actinolite; shiny black cruciform twins of baddeleyite; pristine prisms of utterly colorless and transparent goshenite beryl (to 2.3 cm long, this one for 19 €); butterscotch-colored chondrodite crystals in white calcite matrix; three sharp, colorless sinhalite crystals measuring 4.7, 6.6 and 7.1 mm; and excellent gem-potential danburite, enstatite, hambergite, petalite (16 of these), phenakite, topaz, spinels of all styles, several tourmaline species, etc., etc. If you’ve seen, on Rob Lavinsky’s Arkenstone site, the little collection of gem crystals that Bill Larson assembled during several years’ worth of trips to Burma, you get the idea of what the Crystal Treasure dealership has to offer—in quantity.

Speaking of Arkenstone (www.irocks.com), Rob Lavinsky has recently put up ten very nice specimens of welagonite, and three of the very rare dresserite, which were collected in 1981 at the now-defunct Francon quarry in Montreal, Quebec (for a very full story on Francon, see the January-February 2006 issue). Some of the welagonite specimens are loose single crystals and parallel groups, while others are matrix pieces. In general the welagonite shows the familiar stacked-dinner-plate habit, with individual “stacks” reaching 2.5 cm. The dresserite appears as snow-white spherical aggregates to 2 mm diameter spotted thickly on matrix. Good weloganites (and dresserites) like these have been generally unavailable on the market for many years.

Another veteran dealership, Brad and Elena and Star Van Scriver’s Heliodor, has lately been expanding its website. Although the Prague-based Heliodor folks are always a major presence (and put out the very best candy snacks in their rooms at the Tucson and Denver hotel shows), their site has been a bit skimpy so far—but matters are improving. Abundantly shown right now on www.heliodor1.jodoshared.com are fine, miniature and cabinet-size specimens of contemporary classics in which the Van Scrivers have long excelled, e.g. calcite and fluorite from Dalnegorsk, blushing pink cobalt-rich calcite from Bou Azzer, and of course the superlative vanadinite from Mibladen, Morocco, such as, every time you think that the one you’ve just seen cannot possibly be improved upon, the Van Scrivers come up with even better, more beautiful, crisper and redder, specimens of the material—and often really large, too; see the photo here.

Another veteran dealership, Brad and Elena and Star Van Scriver’s Heliodor, has lately been expanding its website. Although the Prague-based Heliodor folks are always a major presence (and put out the very best candy snacks in their rooms at the Tucson and Denver hotel shows), their site has been a bit skimpy so far—but matters are improving. Abundantly shown right now on www.heliodor1.jodoshared.com are fine, miniature and cabinet-size specimens of contemporary classics in which the Van Scrivers have long excelled, e.g. calcite and fluorite from Dalnegorsk, blushing pink cobalt-rich calcite from Bou Azzer, and of course the superlative vanadinite from Mibladen, Morocco, such as, every time you think that the one you’ve just seen cannot possibly be improved upon, the Van Scrivers come up with even better, more beautiful, crisper and redder, specimens of the material—and often really large, too; see the photo here.

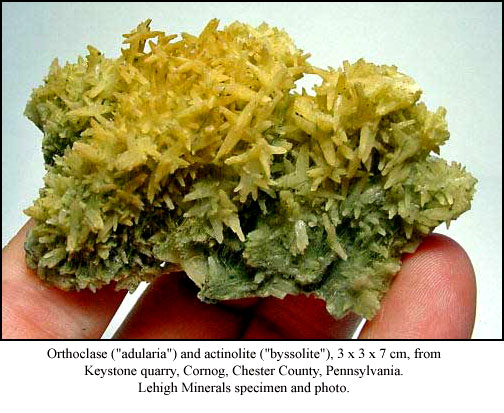

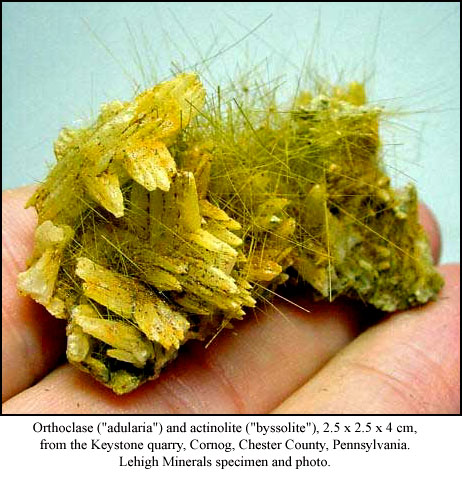

Time now, courtesy of Lehigh Minerals, to familiarize ourselves with the products of a long-gone Pennsylvania locality. Or, in the case of old Pennsylvanians like the present writer, to re-familiarize ourselves with a place which we may not have known well enough, or have visited often enough, in the 1960’s, when it last produced its distinctive, often superb specimens. I refer to the Keystone quarry near the village of Cornog, Chester County, where road-metal rock was taken from a banded hornblende gneiss with interlayered amphibolite and lenses of blue quartz. Commercially active from 1908 to 1968, the Keystone quarry had Alpine-type clefts from which came excellent (though invariably iron oxide-stained) specimens of adularian orthoclase, byssolitic actinolite, clinozoisite and prehnite. Very rarely, too, its clefts gave up world-class crystal clusters of colorless and transparent fluorapatite that, with their inclusions of acicular actinolite, very closely resemble the fluorapatites of the famous Knappenwand, Untersulzbachtal, Austria epidote occurrence. Lehigh Minerals recently purchased a hoard of about 500 “Cornog” specimens from an old Pennsylvania collection; previewed at last year’s Denver show, the hoard, or anyway the best of it, was posted on the website (www.lehighminerals.net) just after the Tucson Show. Opaque milky white adularian orthoclase was found at Cornog as curious-looking reticulated groups of spindle-shaped crystals, these little clusters available with Lehigh as self-contained thumbnails or as thick piles on matrix plates to 7 cm across. Inevitably, the fibrous “byssolite” variety of actinolite accompanies the orthoclase, as cobwebby aggregates around the bases of crystals and/or as individual, delicate, upstanding needles. Clinozoisite comes as dense, parallel groups of very thin, lustrous, gray-green prisms surrounded by byssolitic actinolite or, in a few specimens, as individual, thicker prisms to 5.5 cm long. Spiky little crystals of yellow-green prehnite to a few millimeters, and tiny goethite pseudomorphs after pyrite, sometimes are seen also suspended in the actinolite clouds…but it grieves me to say that this specimen lot includes no fluorapatite specimens (at least that we are to know of). This is a suite which deserves checking-out, at the least for elementary educational reasons, if not also because it may be your first and last chance to score something from this significant, never well enough known, locality.

Time now, courtesy of Lehigh Minerals, to familiarize ourselves with the products of a long-gone Pennsylvania locality. Or, in the case of old Pennsylvanians like the present writer, to re-familiarize ourselves with a place which we may not have known well enough, or have visited often enough, in the 1960’s, when it last produced its distinctive, often superb specimens. I refer to the Keystone quarry near the village of Cornog, Chester County, where road-metal rock was taken from a banded hornblende gneiss with interlayered amphibolite and lenses of blue quartz. Commercially active from 1908 to 1968, the Keystone quarry had Alpine-type clefts from which came excellent (though invariably iron oxide-stained) specimens of adularian orthoclase, byssolitic actinolite, clinozoisite and prehnite. Very rarely, too, its clefts gave up world-class crystal clusters of colorless and transparent fluorapatite that, with their inclusions of acicular actinolite, very closely resemble the fluorapatites of the famous Knappenwand, Untersulzbachtal, Austria epidote occurrence. Lehigh Minerals recently purchased a hoard of about 500 “Cornog” specimens from an old Pennsylvania collection; previewed at last year’s Denver show, the hoard, or anyway the best of it, was posted on the website (www.lehighminerals.net) just after the Tucson Show. Opaque milky white adularian orthoclase was found at Cornog as curious-looking reticulated groups of spindle-shaped crystals, these little clusters available with Lehigh as self-contained thumbnails or as thick piles on matrix plates to 7 cm across. Inevitably, the fibrous “byssolite” variety of actinolite accompanies the orthoclase, as cobwebby aggregates around the bases of crystals and/or as individual, delicate, upstanding needles. Clinozoisite comes as dense, parallel groups of very thin, lustrous, gray-green prisms surrounded by byssolitic actinolite or, in a few specimens, as individual, thicker prisms to 5.5 cm long. Spiky little crystals of yellow-green prehnite to a few millimeters, and tiny goethite pseudomorphs after pyrite, sometimes are seen also suspended in the actinolite clouds…but it grieves me to say that this specimen lot includes no fluorapatite specimens (at least that we are to know of). This is a suite which deserves checking-out, at the least for elementary educational reasons, if not also because it may be your first and last chance to score something from this significant, never well enough known, locality.

While “in” Pennsylvania I’ll pass on word of a brand-new occurrence of wavellite in that state, this word as passed on to me by Joe Polityka, our fearless regular Springfield Show correspondent. After a boundary road had been bulldozed around the Mount Pleasant Hills quarry in Snyder County, in central Pennsylvania, some local collectors found wavellite as lemon-yellow to nickel-green, intergrown spheres, the specimen-style much like that of green Arkansas wavellite and the quality, at its best, at least as good as for the Arkansas material. Specimens so far range from miniature to large-cabinet size. As far as I or Joe knows, Mount Pleasant Hills wavellite is not yet available anywhere on the web, but if it’s as good as They Say, surely, that situation shall change.

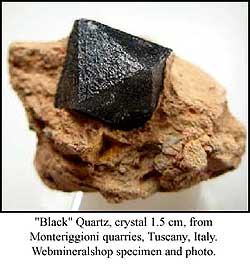

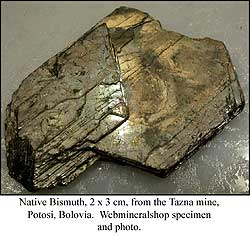

The Italian dealership called Webmineralshop (www.webmineralshop.com) has been mentioned before in this space, and its update of April 3 easily wins it another bow—you know you have an interesting site to browse through when the entry windows say things like “Italian mix,” “Elba mix,” “Eastern Europe mix,” “Raremineralshop,” and “Bismuth and vauxite crystals.” Emerging from the browsing experience, I find that images of sharp, iron-cross-twinned pyrite crystals from Elba are fixed on my retinas; also there are some fairly nice, recently collected specimens of euchroite from classic L’ubietová (Libethen), Slovakia; fine miniature clusters of andradite from Seriphos, Greece; some bright blue vauxite druses from the Siglo XX mine, Bolivia; and some really impressive, bright, loose, platy crystals of native bismuth to 4 cm across, from the Tazna mine, Bolivia. Especially appealing are some miniature-size matrix specimens showing bipyramidal crystals (no prism faces) of “black” quartz from the Monteriggioni quarries in Tuscany. Although slightly rough-surfaced, the quartz crystals are lustrous and quite sharp; they perch pertly in brown, earthy matrix of a calcareous clayey rock called “Grotti breccia,” and, being heavily included by organic material, they really are black, except for a few which show areas of translucent dark gray. According to one of the Webmineralshop staff, these specimens have been collected since the late 1990’s, and the quartz crystals reach 6 cm exceptionally.

The Italian dealership called Webmineralshop (www.webmineralshop.com) has been mentioned before in this space, and its update of April 3 easily wins it another bow—you know you have an interesting site to browse through when the entry windows say things like “Italian mix,” “Elba mix,” “Eastern Europe mix,” “Raremineralshop,” and “Bismuth and vauxite crystals.” Emerging from the browsing experience, I find that images of sharp, iron-cross-twinned pyrite crystals from Elba are fixed on my retinas; also there are some fairly nice, recently collected specimens of euchroite from classic L’ubietová (Libethen), Slovakia; fine miniature clusters of andradite from Seriphos, Greece; some bright blue vauxite druses from the Siglo XX mine, Bolivia; and some really impressive, bright, loose, platy crystals of native bismuth to 4 cm across, from the Tazna mine, Bolivia. Especially appealing are some miniature-size matrix specimens showing bipyramidal crystals (no prism faces) of “black” quartz from the Monteriggioni quarries in Tuscany. Although slightly rough-surfaced, the quartz crystals are lustrous and quite sharp; they perch pertly in brown, earthy matrix of a calcareous clayey rock called “Grotti breccia,” and, being heavily included by organic material, they really are black, except for a few which show areas of translucent dark gray. According to one of the Webmineralshop staff, these specimens have been collected since the late 1990’s, and the quartz crystals reach 6 cm exceptionally.

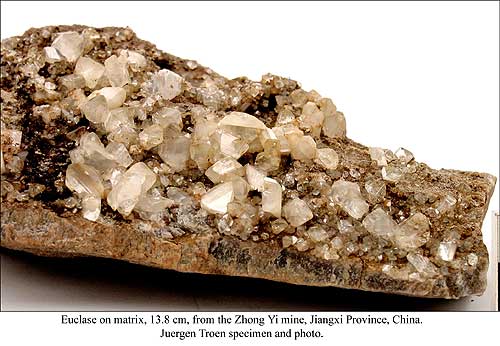

During the Tucson Show, Jürgen Trön spotted a few pulse-quickening new specimens of euclase from China. Reportedly hailing from a locality called the Zhong Yi mine, Jiangxi Province, the specimens appeared at Marty Zinn’s new Quality Inn-Benson Highway show venue, laid out casually on an outside table amid humble acreages of quartz and calcite, and later attempts by Jürgen and others to learn more about the occurrence ran up against something like a Great Wall. A Scovil photo of a superlative thumbnail specimen from the find will accompany the show report in May-June, but some photos that Jürgen has come up with since February might alter consciousness even more—see the one offered here—since they depict matrix slabs to almost 15 cm thoroughly blanketed by sharp, transparent, colorless euclase crystals which approach 2 cm individually. Jürgen tells me that he knows of about 40 other specimens, of which he selected ten for his own dealership (you may contact him at ba1948@bnv-bamberg.de), the rest going to another dealer. These euclase crystals resemble some from the Swiss and Austrian Alps (but are much larger); the only associated crystals noted so far are quartz prisms and a few altered cubes of pyrite.

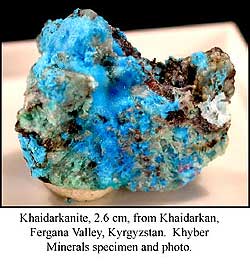

Finally, let’s give it up for the very pretty and very rare new species khaidarkanite, a Cu-Al fluoride-hydroxide apparently known so far only from its type locality, the Khaidarkan mercury-antimony deposit near Khaidarkan in the Fergana Valley of Kyrgyzstan. Khaidarkanite comes as velvety coatings of very finely fibrous, sky-blue crystals on matrix, and thus might make you think, say, of cyanotrichite from the Grandview mine in the Grand Canyon of Arizona. Specimens brought to shows in the West, mostly by Russian dealers, during the past few years have been less than thrilling to look at, as the spots and splashes of khaidarkanite on the mottled brown matrix material have been very sparse. But a batch of specimens now offered on the site of Khyber Minerals (www.khyberminerals) represents a distinct quantum leap in the right direction, showing, as they do, bright blue, furry mats both in tiny vugs and in plateaus between them, achieving perhaps 40% coverage of matrix pieces to 4 cm across. Perhaps, as sometimes happens, specimens of this species will grow more attractive, hence more collectible, as they grow more common.

Contemporary Locality News

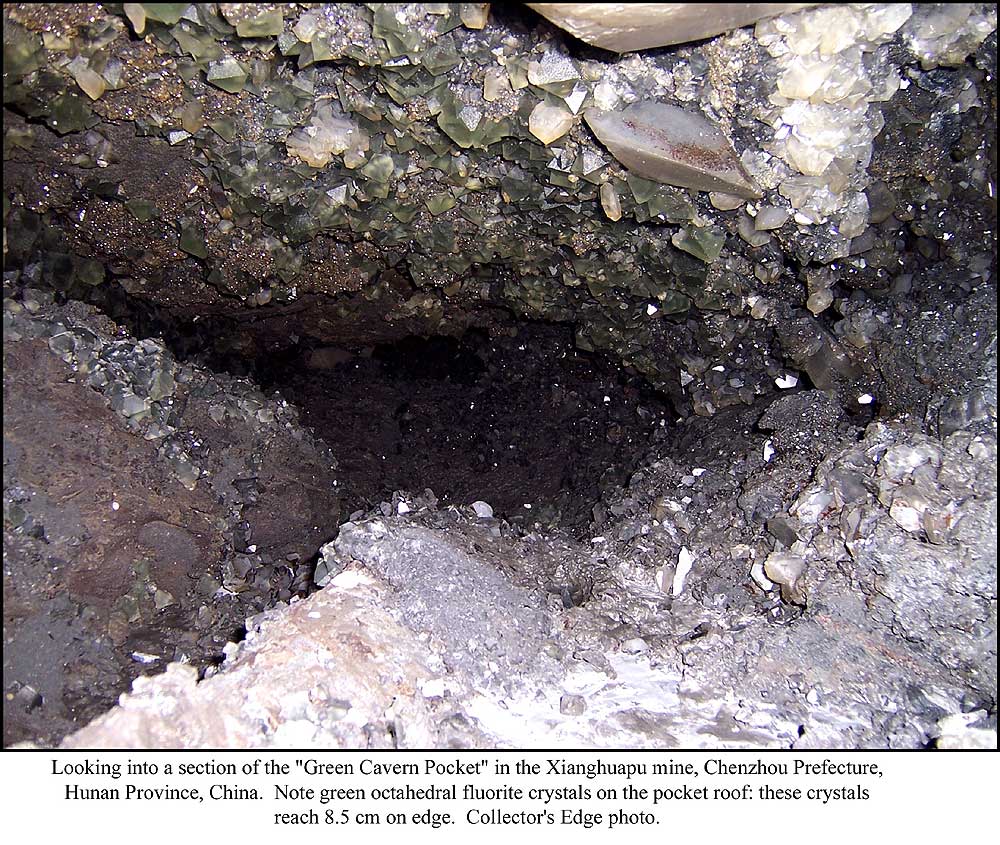

There is only one item of news of this kind, actually, but a large and exciting one, which has come to me via Tom Gressman of the Collector’s Edge dealership (www.collectorsedge.com). One of the world’s most prolific fluorite localities, past or present, is the Xianghuapu mine, Chenzhou Prefecture, Hunan Province, China. This mine lies very near to (but should not be confused with) the larger Xianghualing mine, which also, of course, is a major producer of crystallized fluorite. The Mineralogical Record recently published an article on the Xianghuapu mine: see the “China II” issue (January-February 2007), wherein Berthold Ottens describes his March 2005 visit to witness active collecting in an immense pocket of calcite and green fluorite deep in the mine. Not only did Ottens see many tons’ worth of lovely green fluorite specimens from the pocket, awaiting their handlers and marketers, but, he writes, he heard rumors that other major pocket discoveries were being made elsewhere in the mine complex. From here on I quote from Tom Gressman’s account:

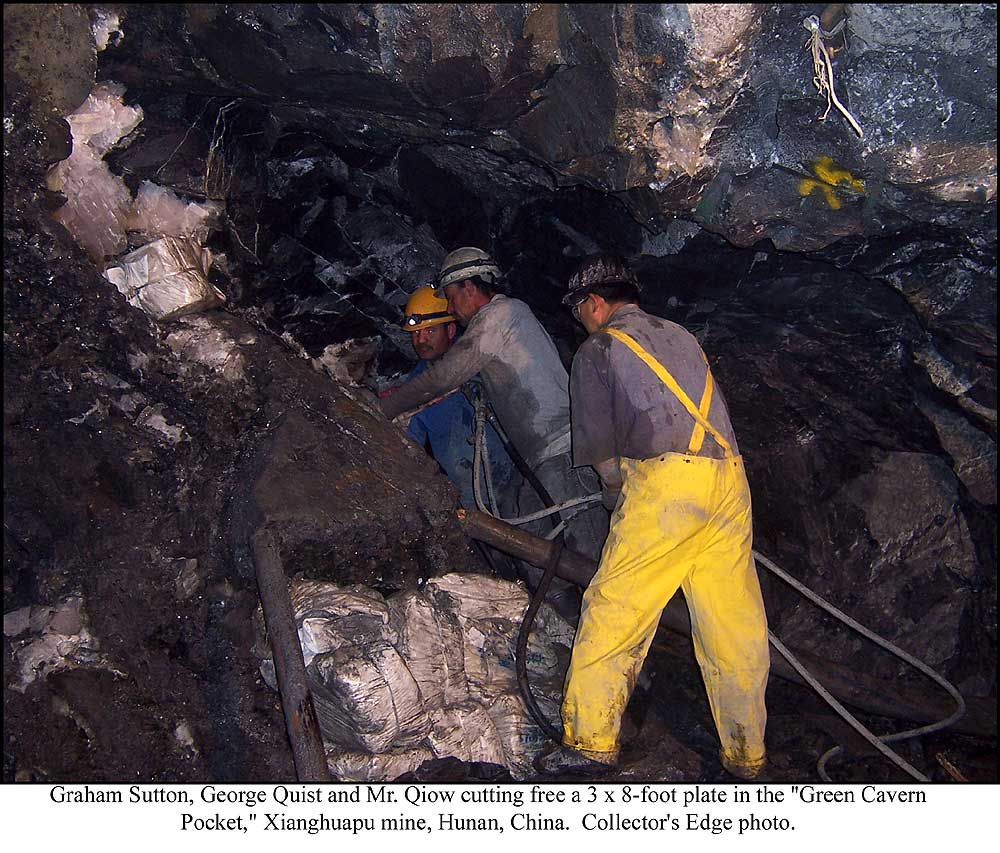

“On March 1 of 2007, a remarkable pocket of green fluorite and white translucent to transparent calcite was discovered in the Xianghuapu mine…Graham Sutton, former General Manager at the successful Sweet Home mine of rhodochrosite fame, and George Quist, both employees of Collector’s Edge, along with six Chinese miners, encountered a pocket 6 to 8 feet in diameter and at least 35 feet long! The pocket, about 200 feet below the surface, was named the “Green Cavern Pocket” because it was lined with green modified octahedral fluorite crystals to 3.5 inches on edge, along with flattened-rhombohedral, translucent to gemmy white calcite crystals up to 16 inches across. The matrix is a black, hard limestone with numerous crinoid fossils.

“Working with his crew, Graham ‘camped out’ overnight underground at the site of the pocket during trips on 3/28/07 and 4/11/07, and the crew collected a significant number of undamaged, pristine cabinet specimens. This exploration project was not without its geopolitical impact, however. Graham was taken in by the Chinese security equivalent of the FBI for interrogation. The security agency wanted to know what Americans were doing in the area, and especially why they were ‘living’ underground. After a half hour or so of ‘discussion,’ Graham was released. No one can ever say that collecting fine minerals is a simple task!

“These aesthetic cabinet specimens are now en route to Collector’s Edge…for further information, contact Steve Behling at (303)-278-9724 X 10, or Graham Sutton at (303)-915-4645.”

Museum News

On April 4, the American Museum of Natural History in New York put on public display what is said to be the largest stibnite specimen ever put on public display anywhere in the world. Yes, we’ve all seen large stibnites, and unfortunately I don’t have this beast’s spatial measurements, but the Museum reports its weight at 1,000 pounds. It sports hundreds of swordlike stibnite crystals rising from matrix, and it is from the Wuning (or Wuling) antimony mine, Jiangxi Province, China (see the article on this mine by Wilson and Behling in the March-April 2002 issue, and see Ottens’s article on “Chinese Stibnite” in January-February 2007). The specimen was donated to the AMNH by New York collector Mark Weill—winner of the Desautels Award (“best rocks in the show”) at Tucson this year—and it will be on show in the Museum’s newly renovated 77th Street Grand Gallery. (While you’re at it, step into the older gallery and pay respects to the supernally great “Newmont azurite” specimen from Tsumeb—one of the finest single mineral specimens of any species in the world.)

Some National Museum of Natural History (Smithsonian) news now will conclude this column’s hodgepodgery of effusions. Between mid-April and Labor Day, an exhibit called “The Lost World of James Smithson” will be on view at the Smithsonian Castle in Washington, D.C. Heather Ewing, Research Associate in the Smithsonian Archives, writes: “Based primarily on Smithson’s mineral notes, one of the only items of his that survived the Smithsonian fire of 1865, [the exhibit] will feature a representative recreation of Smithson’s mineral collection (which was lost in the fire). Paul Powhat…has selected the specimens from the present-day NMNH collections…I believe that the exhibit or some form of it may travel with the Smithsonian Institution to Tucson next year.” Historians of mineral collecting, or just history-sensitive mineral collectors, should find this exhibit of major interest. Furthermore, “…on May 9, in the evening, I [Heather Ewing] will be speaking to the Smithsonian’s Senate of Scientists, also at NMNH, focusing specifically on Smithson as natural scientist. This is open to the public as well, but tickets are $25 and include dinner. This May 9 lecture will also feature my colleague Steven Turner, curator of physical sciences at the National Museum of American History. Steve organized the recreation of some of Smithson’s blowpipe analysis work last year and had it professionally filmed, and we will be showing clips from the film at the talk…it is wonderful to see the blowpipe close up in action.”

Heather Ewing’s book The Lost World of James Smithson: Science, Revolution, and the Birth of the Smithsonian has just been published—look for a review in the Mineralogical Record.

For questions about this column, please email Tom Moore.