ARISTOTLE.

( – 322 B.C.)

Aristotle was the son of Nicomachus, physician to King Amynas II of Macedon. He became a student of Plato, at the Athens Academy, 367-347 B.C.E Afterward he traveled throughout the Greek world, especially Asia Minor, 347-342 B.C.E He was appointed by Phillip II of Macedon to be tutor to his son (later called Alexander the Great). Aristotle founded and was a teacher of the Lyceum (or Peripatos) in Athens, 335-323 B.C.E In 323 B.C.E, he retired to Chalcis upon death of his guardian, Alexander the Great. He is the founder of the systematic study of symbols and logic and theory of symbolism which enabled him to develop logic as a science. He collected facts about the natural world around him through personal observation. These he then recorded in a series of monographs which were handed down through manuscript until the invention of printing. Aristotle, as a teacher, had great influence on his students, with his ideas and ideas attributed to him, becoming the cornerstone of western science and philosophy for one and a half millennia.

Biographical references: Catalogue of Portraits of Naturalists: 123 [5 portraits listed]. • DSB: 1, 250-81 [by L. Minio-Paluello]. • Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th edition. • Nouvelle Biographie Générale (Hoefer). • Poggendorff: 1, col. 61. • Schaedler, Biographisch Handwörterbuch, 1891: 3. • World Who's Who in Science: 61-2.

Lapidarius

1. Latin, 1473.

Lapidarius Aristotilis.-Quomodo virtutes pretiosorum lapidum augmentantur. - Physiognomia. Merseburg, [anonymous printer, probably Lukas Brandis], 20 October 1473.

2°: [a10 b-d8 e6] (unsigned); 40 leaves, the first and last blank.; no pagination. Gothic type, 2 columns, 37 lines. Colophon (39v, col. 2): "Anno dm Millesimo{q}drin= | gentesimoseptuagesimoter | cō in uigilia xj miliū virginū | cōpletū est psens opus In | Ciuitate. Merszborg:."

Contents: Folios 1, Blank.; 2r, "[A5]Tendite a falsis | {\ppwdot}hetis qui ueni= | unt ad uos in ue= | stimentis ouiū. in | trinsecus aūt sunt | lupi rapaces ..."; 39v, col. 1, "Explic liber de phisonomia | liber em diuidit in tres par|tes In {\ p}ma {\plowbar}te tradit vide= | licz Lapidarius aristotilis. | de nouo a greco trāslat9 ... Sc[old aux]'o qūo uirtutes {\ p}ci | oso[old aux] lapi[old aux]' augmentat et al | terat ..."; 39v, col. 2, line 10, "Tercia pars est de ipa met | phisonomia / & incipit ibi | Restat de signis phisomie. | Anno dm Millesimo{q}drin= | gentesimoseptuagesimoter | cō in uigilia xj miliū virginū | cōpletū est psens opus In | Ciuitate. Merszborg:."; 40, Blank.

Edition princeps. Extremely rare. The Lapidarius was the first lapidary printed after the invention of mechanical printing, and this is the second book printed at Merseberg. It is attributed to Aristotle being called the "Lapidarius et Liber de physionomia of Aristotle," but was composed long after his death because the text refers to more recent authorities such as Rasis and Albertus Magnus, and alludes to the mountains of Lombardy, St. Gotthard, a castle in Saxony, and to the river Saale which flows in Franconia and is called the Christian Saale, and that which descends towards Saxony and is known as the pagan Saale. It is a work entirely devoted to precious stones and physiognomy, "written in honor of Wenzel II, king of the Bohemians" [1266-1305]. The manuscript is preservered as a fifteenth-century text in the Public Library, Bern (MS. 513) as an anonomous physiognomy. It is an entirely different text from the Lapidary of Aristotle published by Julius Ruska at Heidelberg in 1912 [which see next entry].

The work is divided into three parts. In the first is treated the Lapidarius of Aristotle in the new translation from the Greek with all the other lapidaries and their statements as to the colors, virtues, and place of generation of each stone. The second part describes how the virtues of precious stones are increased and altered according to diverse situations, such as wearing them on the finger or in the armpit, or combining them with other things and engraving characters on them. The third part is devoted to physiognomy itself.

The printing of this work has been assigned to the printer Lukas Brandis [see note below].

Lukas Brandis. (Born: ; Died: ) German printer. In 1475, Brandis published at Lübeck a world history, which was the first title published in this city.

Bibliographical references: BL [IB.9605.]. • BMC XV: 2, 546 [IB 9605]. • Bonitz, H., Index Aristotelicus. 2. editio. Graz, Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, 1955. viii, 878 p. [Facsimile reprint of the 1870 edition.]. • GW: no. 2389. • Hain, Repertorium Bibliographicum, 1826-38: no. 1777. • Hammer-Jensen, I., "Das sogenannte 4. Buch der `Meteorologie' des Aristoteles", Hermes: Zeitschrift für klassische Philologie, 50, (1915), 113-36. • Klebs, Incunabula Scientifica, 1938: no. 89.1. • Osler, Incunabula Medica, 1923: no. 30. • Pellechet, Catalogue General des Incunables, 1970: no. 1263. • Proctor, Index, 1898-1906: no. 2601. • Riley, L.W., Aristotle texts and commentaries to 1700 in the University of Pennsylvania Library; a catalogue. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, [1961]. 109 p., facsims. ["First appeared in five installments in the University of Pennsylvania Library chronicle, XXII-XXIV (1956-1958)"]. • Schmitt, C.B. and D. Knox, Pseudo-Aristoteles latinus. A guide to Latin works falsely attributed to Aristotle before 1500. London, Warburg Institute, University of London, 1985. vii, 103 p. [Published as: Warburg Institute surveys and texts, 12]: no. 72. • Thorndike, L., "De lapidibus", Ambix, 8, (1960), 6-23. [Historical review of Aristotele's `De Lapidibus' from beginnings through the Renaissance.]. • Thorndike, History of Magic, 1923-58: 2, 266. • Wellmann, Aristoteles de Lapidibus, 1924. (Brandis) ADB. • DBA: I 135, 165-166; II 166, 260. • Jöcher, Gelehrten-Lexikon, 1750-51. • NDB. • WBI.

2. German, 1912 [German transl.].

Das | Steinbuch Des Aristoteles | Mit Literatgeschichtlichen Untersuchungen | Nach Der | Arabischen Handschrifdt Der Bibliothèque Nationale | Herausgegeben Und Übersetzt | Von | Dr. Julius Ruska | Privatdozent An Der Universität Heidelberg | [ornament] | Heidelberg 1912 | Carl Winter's Universitätsbuchhandlung.

8°: [i]-vi, [2], [1]-208 p. Page size: 232 x 160 mm.

Contents: [i-ii], Title page, verso publication information.; [iii], Dedication.; [iv]-vi, Forword.; [1 pg], Errata.; [1 pg], Blank.; [1]-92, Historical investigation.; [93]-125, Arabic text from the Codex, Paris, 2772.; [126]-182, German translation with commentary.; [183]-208, Latin text from the Codex Leodiensis.

Very scarce. Translation with extensive commentary of a work attributed to Aristotle in the Middle Ages, but now recognized as a false work of his. The text was translated by Julius Ferdinand Ruska from an ancient manuscript held in the Bibliothèque Nationale Libary of Paris. It is not an authentic Aristotle treatise but authored under his name in the ninth century, in the Syriac language (by Hunain ibn Innak[?]). An early edition of this work was published also in part ([4], 92 p.) as Ruska's Habilitationsschrift Heidelberg, 1911, with the title: "Untersuchungen über das Steinbuch des Aristoteles."

Bibliographical references: Isis: 1 (19???), 266, 341-50 [review]. • NUC: 20, 627 [NA 0401680]. • Rhode, G., Bibliographie der deutschen Aristotles-Übersetzungen vom Beginn des Buchdrucks bis 1964. Frankfurt am Main, Vittorio Klostermann, 1965: no. 116. • Sinkankas, Gemology Bibliography, 1993: no. 5639. • Thorndike, L., "De lapidibus", Ambix, 8, (1960), 6-23. [Historical review of Aristotele's `De Lapidibus' from beginnings through the Renaissance.]. • Ullmann, M., "Der literarisches Hintergrund des Steinbuches des Aristoteles," (pp. ??-??) in: Actas IV Congresso de Estudos árabes e Islâmicos. Lisboa, 1968.

Meteorologica

3. Latin, 1474 [First edition].

Aristotle Opera.-Meteorologica. Libra I-IV. Padua, Laurentius Canozius for Johannes Philippus Aurelianus et fratres, VIII. Kal. Jul. [24 June] 1474.

2°: [a-c10 d4] (d4 blank); 34l.; no pagination. Two columns, 51 lines to the page. Page size: 436 x 275 mm.

Edition princeps. Extremely rare. The first printed edition of Aristotles collected works, consisting of De Anima, Metaphysica, De Cœlo, De Generatione, Meteorologica, Parva Naturalia, & Physica appeared between 1472 and 1474 from the press of Laurentius Canozius in Padua. The Meteora (often spelled with an `h', Metheora) presents in three books an investigation of "things aloft," and includes studies of the stars, comets, winds, the lower atmostphere, and then proceeds to an account of related phenomena like weather, tides, earthquakes, climatic changes. A fourth book is concerned with chemical change and the properties of matter and bares some measure in mineralogy. Ten diagrams illustrate the text and a map summarizes Aristotle's views on the habitable zones of the earth.

The fourth book of the Meteorologica occupies a strange position in the list of the Stagirite's works. The first three books are concerned with meteorological phenomena as explained by the actions and affectivities of the moist and dry exhalations, and all such phenomena are ascribed to these agencies. Moreover, at the end of the third book a promise is made to furnish a study of the exhalations as they occur inside the earth. There two classes of matter are to be discussed, those bodies that are mined and those that are quarried. But the promised discussion nowhere appears in the extant works of Aristotle. However, around 1200 A.D. a fourth book began to appear in the manuscripts of the Meteorologica. It writing was such that it was accepted as a genuine work of the master, but research in the early 20th century show conclusively that this fourth book is actually the "De Mineralibus" authored by Avicenna.

Avicenna's work is partly a direct translation and partly a résumé of passages in from Avicenna's Kitâb al-shifâ' (Book of the remedy). It was translated by Alfred of Sareshel in the 13th century. On the surface it describes the formation of minerals and mountains. From a scientific point of view, Avicenna's opinions on the formation of stone, rocks, and mountains are remarkably interesting in that they show an astonishing insight into the geological process. He is clear and concise in his remarks on the nature of minerals and in particular is ruthless in his criticism of the alchemists and their attempt to transmute the base metals into gold.

In this the first printing of all four books of Aristotle's Meterologica there is contained a commentary by Averröes [see note below] on Book IV only.

Averröes. (Born: Cordova, Spain, 1126; Died: Morocco, 1198) Arabian philosopher, astronomer & writer on jurisprudence. Averröes (Arabic: Abul Walid Mahommed Ibn Achmed, Ibn Mahommed Ibn Rushd) was educated in his native city, where his father and grandfather had held the office of cadi (judge in civil affairs) and had played an important part in the political history of Andalusia. He devoted himself to jurisprudence, medicine, and mathematics, as well as to philosophy and theology. Under the Califs Abu Jacub Jusuf and his son, Jacub Al Mansur, he enjoyed extraordinary favor at court and was entrusted with several important civil offices at Morocco, Seville, and Cordova. Later he fell into disfavor and was banished with other representatives of learning. Shortly before his death, the edict against philosophers was recalled. Many of his works in logic and metaphysics had, however, been consigned to the flames, so that he left no school, and the end of the dominion of the Moors in Spain, which occurred shortly afterwards, turned the current of Averoism completely into Hebrew and Latin channels, through which it influenced the thought of Christian Europe down to the dawn of the modern era. Averoes' great medical work, "Culliyyat" (of which the Latin title "Colliget" is a corruption) was published as the tenth volume in the Latin edition of Aristotle's works, Venice, 1527. His "Commentaries" on Aristotle, his original philosophical works, and his treatises on theology have come down to us either in Latin or Hebrew translations.

Bibliographical references: Fobes, F.H., "Medieval versions of Aristotle's Meteorology", Classical Philology, 10, (1915), no. 3, 297-314. • GW: no. 2423. • Hain, Repertorium Bibliographicum, 1826-38: no. 1696. • Hellmann, G., Beiträge zur Geschichte der Meteorologie. Berlin, Behrend, 1914-1922. 3 vols. ["Bibliographie der gedruckten Ausgaben, Uebersetzungen und Auslegungen der `Meteorologie' des Aristoteles", 2, (1917), 3-45.; published as: Veröffentlichungen des Königlich Preussischen Meteorologischen Instituts, Nrs. 273, 296 and 315.]. • Horblit: no. 6 [title page reproduced]. • Klebs, Incunabula Scientifica, 1938: no. 91.1. • NUC: 536, 97. • Pellechet, Catalogue General des Incunables, 1970: no. 1202. (Averröes) Catholic Encyclopaedia: 2, ??. • DSB: 12, ?? [under Rushd].

4. Latin, 1489 [Latin].

Prim[us-Quartus] Metheoro[rum]. [Cologne, Heinrich Quentel, 30 May 1489].

Pt. 1: [1], lii, [1], xlvil.; pt. 2: [1], xxxii, [1]l.; pt. 3: [1], xxxiv, [1]l.; pt. 4: [1], xxxvi, [1], xiiiil. [222]l.

Very rare. Section containing the 4 books of Aristotle's Meteorologica with Johannes Versor's [died c1485] commentary. The text was printed by Heinrich Quentell [died 1501].

Bibliographical references: Goff: V-253. • Hain, Repertorium Bibliographicum, 1826-38: 16047*. • Hellmann, G., Beiträge zur Geschichte der Meteorologie. Berlin, Behrend, 1914-1922. 3 vols. ["Bibliographie der gedruckten Ausgaben, Uebersetzungen und Auslegungen der `Meteorologie' des Aristoteles", 2, (1917), 3-45.; published as: Veröffentlichungen des Königlich Preussischen Meteorologischen Instituts, Nrs. 273, 296 and 315.]. • Proctor, Index, 1898-1906: 1295. • Thorndike, L., "Oresme and fourteenth century commentaries on the Meteorologica", Isis, 45, (1954), 145-52. [Treats manuscripts, but also discusses the authenticity of the texts and the authorship of various commentaries.]. • Walsh, 15th Century Printed Books, 1991-2001: 434.

5. Latin, 1491 [Latin].

Meteorologica. [With the commentary, De reactione and De intensione et remissione formarum of Gaietanus de Thienis. Edited by Franciscus de Macerata and Petrus Angelus de Monte Ulmi]. Venice, Joannes and Gregorius de Gregoriis, de Forlivio, 22 October 1491.

2°: a-b8 c-l6 m8; 78l.; no pagination. Printed in red and black. Initial spaces, with guide letters. Leaf [m7v] (colophon): Expliciunt Comentaria super quattuor libros metheorou Aristotelis cu textu eiusdem: [et] duobus tractatibus de re actione: et intesioe [et] remissioe formaru dñi Gaitai de tienis vincentini arctium [et] medicine doctoris clarissimi: suma cu diligentia castigata [et] emendata per sacre theologie bachalarios fratrem Franciscum de macerata [et] fratrem Petrum angelu de monte vlmi ordinis minoru. Venetijs ipressa cura solertissimo [rum] viroru Ioannis de forliuio [et] Gregorij fratrum Anno dñi. M.cccc.lxxxj. die xxij. Mensis octobris. Laus deo.

Very rare. Contains a commentary by Gaetano Tiene [1387-1465] on all four books of the Meteorologica, which has been edited by Macerata de Franciscus and Monte Ulmi de Petrus Angelus. The book itself was printed by Gregorio de' Gregori [fl. 1480-1528].

Bibliographical references: BL [IA.21036]. • BMC XV: 5, 342 [IA.21036]. • Goff: P-399. • GW: no. 2421. • Hain, Repertorium Bibliographicum, 1826-38: 12811*. • Hellmann, G., Beiträge zur Geschichte der Meteorologie. Berlin, Behrend, 1914-1922. 3 vols. ["Bibliographie der gedruckten Ausgaben, Uebersetzungen und Auslegungen der `Meteorologie' des Aristoteles", 2, (1917), 3-45.; published as: Veröffentlichungen des Königlich Preussischen Meteorologischen Instituts, Nrs. 273, 296 and 315.]. • Proctor, Index, 1898-1906: 4526. • Walsh, 15th Century Printed Books, 1991-2001: 1980.

6. Latin, c1492 [Latin].

Meteorologia. Libra 1-4. [Leipzig, Martin Landsberg, c1492.]

2°: A-I6; 54l. 24 lines to the page.

Very rare. This incunbula edition of Aristotle's Meteorologica omits all commentary and presents the text in Latin.

Bibliographical references: GW: no. 2420. • Hain, Repertorium Bibliographicum, 1826-38: no. 1694.

7. Latin, c1496 [Latin].

Meteorologica. Libra I-IV. [With the commentary, De reactione and De intensione et remissione formarum of Gaietanus de Thienis and Quaestiones super meteorologica Aristotelis.]. Venice, Bonetus Locatellus, c1496.

2°: A-H8 I6 AA-GG8; 126l.; [1]-70, 1-54, [2] p. Two columns, 52 lines per page.

Extremely rare. Reissue of the same text first printed in Venice in 1491 and containing the commentary by Gaetano Tiene [1387-1465] on all four books of the Meteorologica, which has been edited by Macerata de Franciscus and Monte Ulmi de Petrus Angelus.

Bibliographical references: GW: no. 2422.

Secretis Secretorum

One of the chief characteristics of medieval literature is the degree to which anonymous and pseudonymous texts were diffused and read. The most striking example is the immense literature in a variety of languages which surrounds Alexander the Great's teacher, the philosopher Aristotle, to whom were attributed many different works with little or no claim to authenticity. In addition to the approximately forty genuine Aristotelian works known in Latin or vernacular versions during the Middle Ages, there were more than a hundred other works attributed to the master at some time during the same centuries. Some of the Latin versions are based upon Greek texts already attributed to Aristotle in Antiquity, others derive from Hebrew or Arabic roots, while others again seem to be original Latin works which became attached to the name of Aristotle at some time in their history. The most widely diffused of all these works is the one which bears the Latin title Secretum Secretorum. It enjoyed immense influence and the widest circulation from at least the tenth (and quite probably significantly before) to the seventeenth century, with more localized influence enduring even longer.

Not all of the Secretis Secretorum editons published under Aristotle's name contain the tract on mineralogy. In fact, apparently none of the dozen or so incunubula editions appear to include it. The first appearance of the work in a published edition of the Secretis Secretorum occurs in the 1501 edition.

8. Latin, 1501 [First edition].

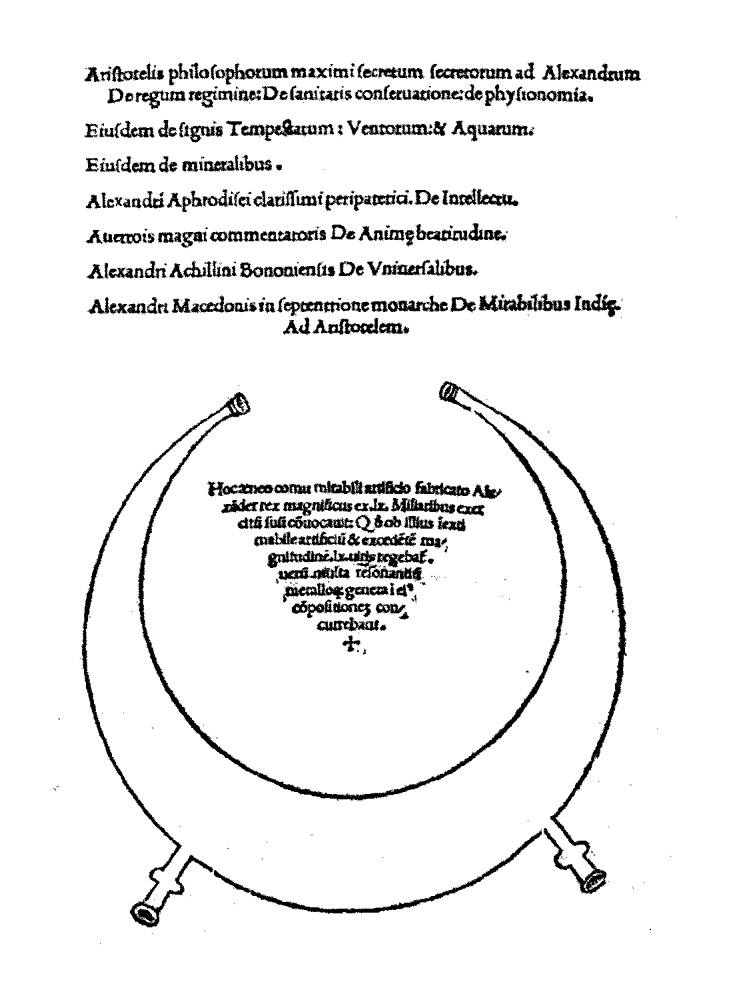

Aristotelis ... secretum secretorum ad Alexandrum / De regum regimine ... / Eiusdem designis tempestatum uentorum & aquarum. / Eiusdem de mineralibus / Alexandri aphrodisei ... de intellectu. / Auerrois ... de anime beatitudine. / Alexandri Achillini ... de Uniuersalibus. / Alexandri macedonis ... de mirabilibus Indiæ / Ad Aristotelem / Woodcut.

2°: a-f6; 36 leaves, in double column. Fol. 36a (colophon): ... impressus Bononiæ Impe / sis Benedicti Hectoris. / Anno. dñi. 1501 ... 26 / octob .... / Printer's mark. Title taken from the first folio.

Very rare. Edited by Alexandri Achillini [see note below], this text contains seven treatises on medicine and philosophy: Secreta secretorum; De signis aquarum, ventorum et tempestatum; De mineralibus; Alexander Aphrodisei de intellectu; Averoes de beatitudine anime; Alexandri Achillini de universalibus and Alexandri Macedonis ad Aristotelem de mirabilibus Indie. Four of these are pseudo-Aristotelian works, which were well known since the 13th century or earlier. The Secreta secretorum is here present in the translation of Philip of Tripoli; the De signis aquarum, ventorum et tempestatum on weather signs, was translated in the 13th century by Bartholomew of Messina; the third work by the pseudo-Aristotle is De mineralibus on gems; the fourth Alexandri Macedonis ad Aristotelem de mirabilibus Indie is a fictitious letter by Alexander the Great to his teacher Aristotle, describing the wonders of India and the East. Three other similar 'Indian tractates' are known, all of them connected with the romance of Alexander the Great at various points in history. All four of them were accepted during the later Middle Ages as reliable literary portraits of the Indians, especially of the Brahmans. They originated in the European culture, and became sources for later tellers and writers of fables. The three remaining treatises in the present work consist of a work by Alexander of Aphrodisias on the intellect, another by Averroes on the beauty of the soul, and a work by Achillini himself on universals.The tract, "De Mineralibus", is based upon a manuscript translation made at the end of the 12th century by Alfred the Englishman [see note below] of Avicenna's work on minerals.The origin of the Secret o f Secrets is veiled in obscurity. All known versions go back to an Arabic original, Kitab Sirr al-'asr, r, of which the earliest extant fragment can be dated A.D. 941. The work itself claims, in the Proem, to have been translated from Greek into Syriac and from Syriac into Arabic by Yahya ibn-al-Bitriq, a well-known ninth-century translator active in the period when the largest number of works was being translated from Greek into Arabic. While it is doubtful, though not impossible, that there was a Greek original, it is clear that the extant versions contain a good deal of Greek material, including a certain amount which derives from genuine Aristotelian doctrine. It also, however, contains much which certainly is traceable to Middle Eastern Islamic sources.In structure the work takes the form of an extended letter from Aristotle to Alexander the Great, which was sent to the king while he was engaged in conquering Persia. It is thus parallel to a number of other extant letters, which purport to be epistolory exchanges between the two eminent figures, of which several exist in Greek. The Secret, as it has come down to us, evidently underwent a long period of gestation. It probably originated as a `Mirror for Princes', a familiar medieval literary form in which a wise man (Aristotle) offers moral and political advice to an eminent political leader (Alexander). It thus contains much specific advice on how the king as handled the many requiremcents of his office. For example, it deals with how the king is to choose and manage his advisors, what diet he should follow, how he should dress, etc. The Secret, as it has come down to us contains much else besides. Probably through a long period of accretion it gradually became a sort of encyclopedic work comprising, in addition to its original moral and political component, much miscellaneous information on occult and pseudo-scientific subjects. Thus there are sections of astrology, physiognomy, alchemy, and magic, in addition to rather detailed medical sections.All known versions derive from one of two Arabic versions, which are extent in a total of about fifty manuscripts. One of the versions is divided into either seven or eight books and is known as the Short Form in Manzalaoui's classification, while the other is in ten books and is known as the Long Form. It was ultimately translated into many different languages including Hebrew, Turkish, Latin, Russian, Czech, Croatian, German, Icelandic, English, Castillian, Catalan, Portuguese, French, and Italian. In some of these languages there are several versions, and in English there are as many as nine, though not all of them are complete. The Latin versions undoubtedly had the greatest fortuna and were the basis for later translations into European vernacular languages. The Russian translation, however, is from a Hebrew version.There are two basic Latin versions, one made in the mid-twelfth century by John of Seville (Joannes Hispalensis) and extant in some hundred and fifty copies, the other made during the first half of the thirteenth century by Philippus Tripolitanus and surviving in more than three hundred and fifty manuscripts. These versions, both in their Latin form and in the many vernacular translations which came from them, were exceedingly widely read for more than four centuries in many different intellectual contexts. Among the major figures of the High Middle Ages who read the work carefully are Albert the Great and Roger Bacon, who wrote a Latin commentary on the Secret. Owing to its encyclopedic nature it was of interest to readers in many different fields ranging from political theory to alchemy, from physiognomy to popular moral philosophy.Though much work has been done previously on many aspects of the Secret, we have by no means reached the stage where one can confidently place the work with its myriad ramifications in its proper historical context. Because it was transmitted in so many diverse cultures and in so many different linguistic and structural forms, to understand fully its overall historical position is beyond the capabilities of any single scholar. There are many unsolved problems of all sorts, ranging from the work's sources to the precise relationship between the various versions in many different languages.

Alessandro Achillini. (Born: Bologna, Italy, 20 October 1463; Died: Bologna, Italy, 1512) Italian philosopher & classical scholar. Achillini studied philosophy and medicine at the university of Bologna, where he became a celebrated lecturer both in medicine and in philosophy. From 1506 to 1508, he also taught at Padua. For his commentaries and editorial work, he was styled the second Aristotle. His philosophical works were printed in one volume folio, at Venice, in 1508, and reprinted with considerable additions in 1545, 1551 and 1568. He was also distinguished as an anatomist.

Alfred the Englishman. (Born: ; Died: ) English translator. Also called Alfred of Sareshel and Alfred Angilicus, was one of the English scholastics who was especially important as a translator of (originally) Greek works from Arabic to Latin. His renderings of Aristotle's works occurred during the late 12th century.

Bibliographical references: BL [no copy listed]. • CBN: 4, 98. • Holmyard, E.J., "Arabic text of Avicenna's Mineralia", Nature, 117, (1926), 305. • NLM 16th Century Books (Durling): no. ????. • NUC: 536, 96 [NS 0275529]. • Ryan, W.F. and C.B. Schmitt, eds., Pseudo-Aristotle, the Secret of secrets: sources and influences. London, Warburg Institute, University of London, 1982. 148 p., illus. • Shaaber, Sixteenth Century Imprints, 1976: A-760. • Thorndike, L., "De lapidibus", Ambix, 8, (1960), 6-23. [Historical review of Aristotele's `De Lapidibus' from beginnings through the Renaissance.]. • Thorndike, History of Magic, 1923-58: 2, 246-78. • Williams, S.J., The secret of secrets: the scholarly career of a pseudo-Aristotelian text in the Latin Middle Ages. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, c2003. (Achillini) Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th edition. • Nouvelle Biographie Générale (Hoefer). (Alfred the Englishman) DNB: 1, 285. • Haskins, C.H., Studies in mediaeval science. 2nd edition. London, Cambridge/Harvard University Press, 1927. xx, 411 p [pp. 128-34].

9. Latin, c1503 [Latin].

Aristotelis philosophorum maximi De secretis secretorum ad Alexandrum opusculum. Eiusdem De regum regimine. Eiusdem De sanitatis conservatione. Eiusdem De physionomia. Eiusdem De signis tempestatum. Eiusdem De mineralibus. Alexandri Aphrodisei clarissimi perepatetici De intellectu. Auerroys magni commentatoris De animae beatitudine. Alexandri Achillini Bononiensis De universalibus. Alexandri Macedonis in Septentrione monarchae De mirabilibus Indiae ad Aristotelem. [Venetiis, 150-?]

2°: A-G[sharp], a-g[sharp] (verso blank); 56l. Colophon: Explicit septisegmentatum opus ab Alexandro Achillino ... ut non amplius in tenebris latitaret editus. Et impressus Venetiis per Bernardinum Venetum de Vitalibus.

Very rare. Edited by Alexandri Achillini. Reprint of 1501 edition.

Bibliographical references: NUC: 536, 96 [NS 0375500].

10. Latin, 1505 [Latin].

Utilissimus liber ari | stotelis de secre | tis secreto- | rum.

8°: a-e8 f4. [87] p. Colophon: Impressum in nobilissima ciuitate Burgeñ, per Andream de Burgos, cum maxima diligentia correptum, anno a natiui Domini millesimo quingentesimo quinto vicessima sexta die mensis junij]. Device of printer? beneath colophon.

Rare. Translated by Philippus Clericus.

Bibliographical references: BL [C.62.c.30.].

11. Latin, 1516 [Latin].

Aristotelis philosophorum maximi secretum secretorum ad Alexandrum | De regum regimine: De sanitatis conseruatione: de physionomia. | Eiusdem de signis Tempestatum: Ventorum: & Aquarum. | Eiusdem de mineralibus. | Alexandri Aphrodisei clarissimi peripatetici. De Intellectu. | Auerrois magni commentatoris De Animę beatitudine. | Alexandri Achillini Bononiensis De Vniuersalibus. | Alexandri Macedonis in septentrione monarche De Mirabilibus Indię. | Ad Aristotelem. | [...10 lines contained with the ornament of Alexander's horn...].

2°: 36l. Impensis Benedicti Hectoris: Bononię, 1516. Illustration on title page (Alexander's horn). Printer's device beneath colophon.

Rare. Edited by Alexandri Achillini. Reprints the text of of the 1501 edition.

Bibliographical references: BL [1482.f.21.]. • NUC: 536, 96 [NS 0375531].

12. Latin, 1520 [Latin].

[Contained within a black ornamental box:] [in red:] Secre | ta Se | creto | rvm | Aristo | Telis | [Below the ornamental box, in black:] Cum priuilegio.

12°: A-O8, Q4 (last blank); 115l.; [i]-cxiiil., [4] p. Title in red within black ornamental border; initials; printer's device on last page. Black letter. Numbered leaves printed on both sides. Leaves lxxix-lxxx and xcii erroneously numbered lxxxi-lxxxii and xc respectively. "Explicit septisegmentatum opus ab Alexandro Achillino ambas ordinarias & philosophie et medicine theorice publice docente: vt non amplius in tenebris latitaret editus [sic]": verso of leaf [cxiv]. Colophon: Explicit septisegmentatum opus ab Alexandro Achillino ... editus [sic]. Et impressus Parisiis Anno domino 1520.

Rare. Edited by Alexandri Achillini. Reprints the text of of the 1501 edition.

Bibliographical references: BL [C.19.a.34.]. • NUC: 536, 97 [NS 0375510].

13. Latin, 1528 [Latin].

Secreta secretorum Aristotelis.- Maximi philosophi Aristotelis de Signis aquarum, ven orum et tempestatum.- Maximi philosophi Aristotelis de Mineralibus.- Alexandri Aphrodisei de Intellectu.- Ayerrois de Beatitudine anime.- Alexandri Achillini, ... de Universalibus.- Alexandri Macedonis ad Aristotelem de Mirabilibus Indie. Lugduni, In ædibus Antonii Blanchard, anno dñi 1528 die xxiij mensis Martÿ.

8°: A-K8 L4; 83l.; [i]-lxxxiijl., gothic characters. Title-page decorated with woodcut border, some woodcut initials and woodcut printer's device on verso last page. Imprint from colophon. Colophon: Explicit Septisegmentatum opus ab Alexandro Achillino ... Lugduni, Impressus in edibus Antonii Blanchard, 1528. Printer's device of Louis Martin on final p. Title within ornamental woodcut. Woodcut initials. border.

Rare. Edited by Alexandri Achillini. Reprints the text of of the 1501 edition.

Bibliographical references: Baudrier, Bibliographie Lyonnaise, 1895: 5, 104. • CBN: 4, 98. • Index Aureliensis: 107.903 [gives Antonius Blanchard as the printer]. • NLM 16th Century Books (Durling): no. 270. • NUC: 536, 97 [NS 0375513]. • Stillwell, Awakening Interest in Science, 1970: no. 578. • Thorndike, History of Magic, 1923-58: 5, 47-53.

14. Latin, 1555 [Latin].

Secretvm | Secretorvm | Aristotelis Ad Alexandrvm | Magnum, cum eiusdem Tractatu de | Animæ immortalitate nunc | primùm adiecto. | A Francisco Storella Alexanense Philosopho ad | ueterum exemplarium fidem eastigatum, atq; | pulcherrimis anntationibus illustratum. | Alexandri Magni ad Aristotelem epistola de |admirabilibus Indiæ, pre eundem Storellam castigata. | Accedvnt præterea duo Tractatus, scilicet Hippo= | cratis Secreta secretorum, & Auerrois Libellus de Vene | nis, Qui penè extincti, ab eodem Storella castigati iam al= | Orco reaocantur. | Ad Hectorem Pignatel= | lum Illustriß. Vibonensium Ducem. | [ornament].

8°: †-$††$4 A-R4; 76l.; no pagination (i.e., [152] p.). Colophon: Mathiam [sic] Cancer Neapoli, 1555.

Rare. Edited by Franciscus Maria Storella [see note below], this is the best edited text of Aristotle's Secretum before modern scholarship. It is a rare edition, with only a handful of copies known to be extant. Moreover, there are two variants, one having a Naples and the other a Venetian imprint. The work is dedicated to Ettore Pignatelli, Duke of Monteleone, and contains a detailed preface, and annotations to the text.

The most significant improvement of the work is that Storella attempted in some measure to create a complete and critical text. He incorporated the information found in the Achillini edition of 1501 (reprinted 1516, 1520, and 1528). He also speaks explicitly of the abbreviated edition published by Franciscus Taegius at Pavia in 1516. Storella also claims to have used several manuscripts in preparing the text. However, Schmitt (1982) says: "On the whole Storella's efforts to improve the text seem to have been somewhat misguided and not really based on any overall understanding of how to go about it. Nevertheless, he made an attempt, and the text he printed was more complete than previous ones."

Franciscus Maria Storella. (Born: Alessano, near Lecce, Italy, c1525; Died: Naples, Italy, 1575) Italian classical scholar. Storella took a degree at Padua in 1549 and later taught at the universities of Salerno and Naples. He published a number of philosophical works, usually commentaries on ancient authorities.

Bibliographical references: BL [8463.aa.31.]. • NLM 16th Century Books (Durling): no. 297. • Schmitt, C.B., "Francesco Storella and the last printed edition of the Latin `Secretum Secretorum' (1555)" (pp. 124-131), in: Ryan, W.F. and C.B. Schmitt, Pseudo-Aristotle the Secret of Secrets, sources and influences. London, The Warburg Institute, University of London, 1982. (Storella) Antonaci, A., Francesco Storeela: filosofo salentino de Cinquecento. Galatina, 1966. [Published as: Università di Bari, pubblicazioni dell'Instituto di Filosofia, 9.].

German editions

15. German, 1530 [German transl.].

Das aller edlest unnd bewertest Regiment der Gesundtheit, auch von allen verporgnen Künsten unnd Künigklichen Regimenten Aristotelis, das er dem grossmechtigen Künig Alexandro zu geschriben hat. Auss arabischer Sprach durch Mayster Philipsen, dem Bischoff von Valentia ... in das Latein verwandelt. Nachmals auss dem Latein in das Teutsch gebracht, bey Doctor Johann Lorchner ... nach seinem Tod geschriben gefunden. Zu Auffenthaltung und Fristung in Gesundheit menschlichem Leben zu Gut durch Johann Besolt in Truck verordnet. [Augspurg, Heynrich Stayner] 1530.

4°: A3 B-M4 N2; [6], I-XLVIl., illus. Very scarce.

Contents: From Rhode (1965): [A1r], Title page.; [A1v], Vorrede.; A2r-A3v, Register=contents.; I-II, "Ein vorrede eynes Maysters, de das Buechlin einem Künig sugesandt hat, darinnen dann fast seere gelobet würdt der hochgeacht unnd natürlich Mayster Ar."; II-XLVI, Translation.

Bibliographical references: BL [1166.f.25.]. • NLM 16th Century Books (Durling): no. 298. • NUC. • Rhode, G., Bibliographie der deutschen Aristotles-Übersetzungen vom Beginn des Buchdrucks bis 1964. Frankfurt am Main, Vittorio Klostermann, 1965: no. 189. • Shaaber, Sixteenth Century Imprints, 1976: A-761. • Wellcome Catalog (Books): 1, no. 457.

16. German, 1531 [German transl., reissue].

Das aller edlest und bewertest Regiment der Gesundtheyt, auch von allen verborgen Künsten unnd künigklichen Regimenten Aristotelis ... Auss arabischer Sprach durch Meister Philipsen, dem Bischoff vonn Valentia ... in das Latein verwandlet. Nachmals auss dem Latein in das Teütsch gebracht, bey Doctor Johann Lorchner ... nach seinem Tod geschriben gefunden. Zu Auffenthaltung unnd Fristung yn Gesundtheit menschlichem Lebenn zu Gutt durch Johann Besolt in Truck verordnet. [Augspurg, Heynrich Stayner] 1531.

4°: [6], I-XLVIl., illus. Very scarce.

Contents: From Rhode (1965): [A1r], Title page.; [A1v], Vorrede.; A2r-A3v, Register=contents.; I-II, "Ein vorrede eynes Maysters, de das Buechlin einem Künig sugesandt hat, darinnen dann fast seere gelobet würdt der hochgeacht unnd natürlich Mayster Ar."; II-XLVIII, Translation.

Bibliographical references: NLM 16th Century Books (Durling): no. 299. • NUC. • Rhode, G., Bibliographie der deutschen Aristotles-Übersetzungen vom Beginn des Buchdrucks bis 1964. Frankfurt am Main, Vittorio Klostermann, 1965: no. 190. • Wellcome Catalog (Books): 1, no. 458.

17. German, 1532 [German transl., reissue].

Das aller edlest unnd bewertest Regiment der Gesundtheit, auch von allen verporgnen Künsten unnd Künigklichen Regimenten Aristotelis, das er dem grossmechtigen Künig Alexandro zu geschriben hat. Auss arabischer Sprach durch Mayster Philipsen, dem Bischoff von Valentia ... in das Latein verwandelt. Nachmals auss dem Latein in das Teutsch gebracht, bey Doctor Johann Lorchner ... nach seinem Tod geschriben gefunden. Zu Auffenthaltung und Fristung in Gesundheit menschlichem Leben zu Gut durch Johann Besolt in Truck verordnet. [Augspurg, Heynrich Stayner] 1532.

4°: [6], I-XLVIIIl., illus.

Contents: From Rhode (1965): [A1r], Title page.; [A1v], Vorrede.; A2r-A3v, Register=contents.; I-II, "Ein vorrede eynes Maysters, de das Buechlin einem Künig sugesandt hat, darinnen dann fast seere gelobet würdt der hochgeacht unnd natürlich Mayster Ar."; II-XLVIII, Translation.

Very scarce. Johann Lorchner, translator.

Bibliographical references: NLM 16th Century Books (Durling): no. 300.

Marbodi liber lapidum seu de gemmis, varietate lectionis et perpetua annotatione illustratis a Iohanne Beckmanno. ... ad Aristotelis Auscultationes mirabiles ... (Gottingæ, 1799).See under: Marbode, Bishop Of Rennes..