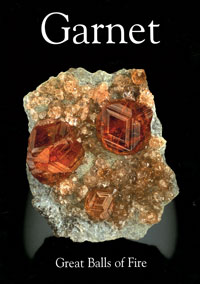

It is getting harder to write original-sounding reviews of new volumes in the ExtraLapis English series, not because their quality is falling off—emphatically that is not the case—but because in many past reviews the apt superlatives have already done duty, and yet all still apply. Garnet: Great Balls of Fire (Number 11 in the series) is, like the others, a great burst of first-rate color photography and expert graphics, a knowledge-broadening treat for the mind, and a medley of fun facts dispersed throughout the quirkily organized chapters (this playful, not-quite-regular organization being by now a trademark of ExtraLapis English productions). For Garnet, Gloria Staebler and Günther Neumeier are joined by four co-editors in marshalling contributions by 24 authors and 40 illustrators, who all together explicate the 15 species of the garnet group: their chemical and crystallographic attributes, geologic settings, worldwide occurrences, history, lore, gemstone uses…and whatever combinations of these lead to interesting chapter arrangements. The project is touchingly dedicated to Mick Cooper (1946-2008), “author, photographer, editor, advisor and humorist,” who helped with past ExtraLapis English projects and is, in the painful but valid cliché, greatly missed by all who knew him.

The introductory chapter, by Smithsonian collection manager Paul Powhat, is called “The Garnet Group: Fifteen Species, Endless Variety.” To help memory order the six most important species, Powhat recommends the old nonce words “pyralspite” and “ugrandite,” respectively for pyrope-almandine-spessartine, with Al in the second cation site, and uvarovite-grossular-andradite, with Ca in the first cation site (I recall consciously and earnestly learning these terms as a child, and now it’s nice to see them again in such a respectable setting).

In the next chapter come “The Rare Garnets,” including such oddities as morimotoite, katoite, calderite, majorite, knorringite—all of which are described concisely, and their worldwide occurrences listed. And here’s what I mean about fun facts: we are authoritatively clued in about those intriguing, earthy gray-brown pseudocrystals from Siberia which are sometimes called “achtaragdite”: they are pseudomorphs of an intermediary solid solution between grossular and katoite after euhedral crystals of mayenite, an extremely rare, poorly characterized Ca-Al oxide. Refine or rewrite your labels accordingly.

For each of the six major garnet species there is a “classic” chapter—e.g. “Classic Garnets: Almandine”—followed by one or more chapters on localities and/or pertinent history and lore. For almandine there’s a chapter on “New England Garnet” (Russ Behnke), with photos of specimens of the wonderful old-timers from Russell, Massachusetts, and a chapter on “Idaho’s ‘Star’ Garnet” (Mickey E. Gunter), offering well-illustrated discussion of what causes asterism in these well-known lovelies. Apropos of some species there are whole chapters on major localities: thus, following “Classic Garnets: Grossular” (Joachim Zang and Thomas Fehr) we find “Jeffrey and Lac d’Amiante” (Marco Amabili, Francesco Spertini and Marc B. Auguste) and “Grossular from Mali” (Bill Dameron); following “Classic Garnets: Spessartine” (six authors) we find “Spessartine from Tongbei” (Bert Ottens). For the most part pyrope does not occur in collectible crystals; nevertheless, in “Pyrope from the Dora-Maira Massif” (Gilla Simon) collectors can learn about a geologically unique occurrence in Italy, and in “The Fiery-Eyed Volcanoes of Bohemia” (Jirí Kouřimský and Jaroslav Hyršl) there’s a sketch of the 2,000-year history of mining Bohemian gem pyropes which originate in Tertiary-age volcanic rocks.

Along the way there are chapters addressing subjects ranging through “Synthetic Garnet: Lasers and Imitation Gemstones” (Lothar Ackerman), “The Microworld of Garnet: Fingerprints, Fans and Haloes” (John I. Koivula), and “Anthrax, Carbunculus, and Granatus: Garnet in Ancient and Medieval Times” (H. Albert Gilg)—say, how about those elegant, 1.5 cm-wide garnet/gold figures of bees, buried with Merovingian monarch Childeric I (ca. 440 – ca. 481) but stolen, all but two, from the Bibliothèque Royale in Paris in 1831, and never recovered?

Of course I’ve omitted mention of plenty of other garnet-related topics which pop up throughout the 22 chapters that fill these 98 pages—and most topics are accompanied by beautiful illustrations. The book is loaded with pictures of world-class garnet specimens, and topping off the mind-feast is a bibliography of 123 entries. Great balls of fire! Get a copy of this one while (as they say) supplies last.

Thomas P. Moore