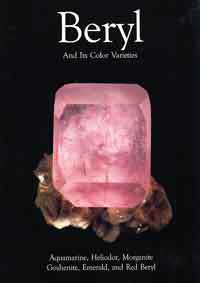

Amazing but true—the series of English ExtraLapis booklets has already reached number seven. Not so amazingly (or even surprisingly), Beryl and its Color Varieties is a lavish collection of beautiful specimen pictures, thorough and well-organized locality information, authoritative mineralogical data accompanied by excellent graphics, and well selected, just slightly quirky assemblages of observations on the topic at hand. To say that this is the third of the seven booklets to show a beautiful beryl specimen on its cover is merely to note a factoid, not to complain of redundancy, for any overlaps here with Emeralds of the World (ExtraLapis #2) and Pakistan: Minerals, Mountains & Majesty (ExtraLapis #6) are mild and unobjectionable. It seems that each English ExtraLapis is more self-assured and more magisterial than the one before, and is at least as much fun to read.

We lead off with science, as the first six chapters cover the mineralogy of the beryl group; explicate and illustrate the cyclosilicate crystal structure; explain how beryl’s color varieties reflect the presence of trace chromophores; and (more thoroughly than any other reference I know) introduce the other members of the beryl group. Can you name these four very rare species, and do you know their major localities, typical parageneses, crystal habits, physical and optical properties, etc.? Well, okay, you know the glamorous pezzottaite, but here too are bazzite (long-prismatic, deep blue microcrystals, from the Alps), stoppaniite (from a pyroclastic bed in Italy) and indialite (dimorphous with cordierite, from a coal seam in India). The account of the discovery, first mining, and first marketing of pezzottaite (contributed by eponymous Federico Pezzotta himself) nicely complements the formal species description in vol. 35 no. 5 of the Mineralogical Record.

For most of the rest of the work we are taken on an extraordinarily thorough world- locality tour—indeed, this seems the most exhaustive so far of the several world-peregrinations that English ExtraLapis readers have been taken on. We touch down at hundreds of places, historically old or new, culturally long-fabled or virginal, geologically simple or complex, where specimen crystals of colored beryl (and gem rough material, of course) have been found. Appropriate experts, the authors of individual chapters, are on hand to guide us: thus, Mark Jacobsen takes us to Colorado, and Tony Potucek to Idaho (Potucek’s “Best of the Rockies” chapter is up-to-date enough to mention the astonishing find of aquamarine matrix specimens on Mount Antero in July, 2004); we tour the pegmatites of New England with Bruce Jarnot and of southern California with Jesse Fisher; with Peter Lyckberg we penetrate the central Ural and Transbaikal gem districts, and cast long glances at the Izumrudnye Kopi emerald field of Russia and the Volodarsk-Volynskiy heliodor occurrence in Ukraine. In another chapter, Lyckberg describes an exciting new find of gemmy green beryl crystals in Finland, while in yet another, Lee A. Groat displays pictures of gem beryl specimens (including emeralds) and gem beryl prospect diggings in forbidding, ice-scoured places we’ve never heard of in Canada. Chinese gem beryl localities are surveyed thoroughly by Guanghua Liu (with pictures of breathtaking beryl specimens from Xuebaoding Mountain), and there are overviews, with many stops for specifics, of Australian gem beryl (Dermot Henry), southern African gem beryl (Bruce Cairncross), Bolivian and Colombian gem beryl (Alfredo Petrov, Rupert Hochleitner); trusty red beryl from Utah (“Skip” Simmons, Al Falster); and Brazilian gem beryl (Luis Menezes). And all the while the specimen pictures, on-site shots, and helpful locality maps (Menezes’ map of the pegmatite districts of Minas Gerais is especially crisp and detailed) just keep on coming.

Two chapters on yellow, “heliodor” beryl are suggestively juxtaposed: one, by Michael Wise, describes processes, natural and artificial, of color-inducement for heliodor, and the other, by Fersman Museum curator Dmitriy Belakovskiy, concerns the beautiful gemmy crystals which have come onto the market during the last ten years or so, presumably from a place called Zelatoya Vada, Tajikistan. Belakovskiy describes the history of his encounters with these mysterious deep yellow crystals—it is a history of puzzlement culminating in his unsuccessful attempt, during a visit to Tajikistan’s Pamir Mountains, to find the producing pegmatite. Reluctantly Belakovskiy concludes that something is very fishy indeed about “this material from a Tajiki locality with a Russian name that was being sold by nearly everyone except for dealers from Russia and Tajikistan”; he remarks, too, that the specimens showing prismatic crystals look, except for their color, exactly like Pakistani aquamarine, and that those showing tabular crystals on muscovite look, except for their color, exactly like “Ping Wu mine” (i.e. Xuebaoding Mountain) beryl specimens. Readers who, like this reviewer, have come to cherish their specimens of “Tajikistan heliodor” will feel saddened but grateful to this publication for its investigative reporting on this subject.

The ExtraLapis concludes with two chapters as independently interesting as they are dramatically unrelated: one on grading and pricing gem beryl (John Bradshaw), the other on the chemistry and uses of the element beryllium (Lee Van Iderstine and Michael Huber). As usual, the very final pages are devoted to a communal bibliography for all articles (138 titles this time!), a list of authors’ addresses, and five commercial ads.

As with the other six entries in the English ExtraLapis series, this new edition is glossy and beautiful, with plenty of interesting and authoritative content for the mineral collector. Who could ask for more?

Thomas P. Moore